NAT Traversal: Difference between revisions

UPnP |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 156: | Line 156: | ||

<li>Rosenberg: Interactive Connection Establishment (ICE), Internet Draft ([http://www.ietf.org/internet-drafts/draft-ietf-mmusic-ice-06.txt link])</li> |

<li>Rosenberg: Interactive Connection Establishment (ICE), Internet Draft ([http://www.ietf.org/internet-drafts/draft-ietf-mmusic-ice-06.txt link])</li> |

||

<li>Schulzrinne: diverse documents concerning NAT and SIP, e.g. NAT Types.pdf ([http://www.cs.columbia.edu/~hgs/teaching/ais/slides/ NAT and SIP])</li> |

<li>Schulzrinne: diverse documents concerning NAT and SIP, e.g. NAT Types.pdf ([http://www.cs.columbia.edu/~hgs/teaching/ais/slides/ NAT and SIP])</li> |

||

<li>STUN Client und Server ([http://sourceforge.net/projects/stun/ link])</li> |

|||

<li></li> |

|||

<li></li> |

<li></li> |

||

</ul> |

</ul> |

||

Revision as of 15:50, 9 March 2006

Note: work in progress

Overview

NAT (Network Address Translation) is widely used to connect private networks to the internet. The main idea is to map several private IP addresses to only one public IP address. Having in mind that P2P network clients should be able to communicate with each other, one basic question comes into mind: how can internet hosts communicate with a host in a private network? We will first have a look at NAT itself and problems it brings. Then, we show how to traverse NATs by either changing router's configuration or by using other tricks.

Network Address Translation

A network address is simply the IP address ( + Port number for UDP/TCP). A NAT router receives an incoming IP packet, saves the address in its NAT table, rewrites sender address to one of its public addresses and sends the packet to the destination address. Now, the NAT router accepts incoming packets on this public address (NAT endpoint). These packets are forwarded to the private host. The most important facts are:

- The mapping depends on the sender's port number. If the private host uses two different outgoing port numbers, the NAT endpoints will differ.

- The private host has to send first. Otherwise no incoming packets will be forwarded to the private host.

- The client does not know all that... (NAT should be completely transparent to the client)

The behavior of the NAT router is not standardized. The only thing that works with every NAT router is simple request and answer. That means the remote host answers a request using the port number the client used for its request. Some NATs allow replies from other ports or even hosts, some use different endpoint mappings for every session.

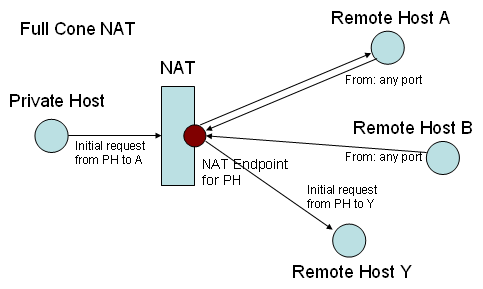

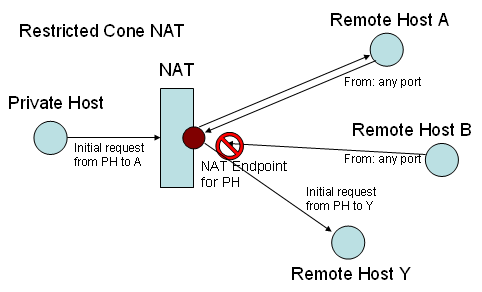

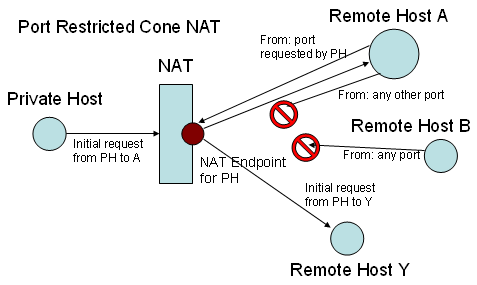

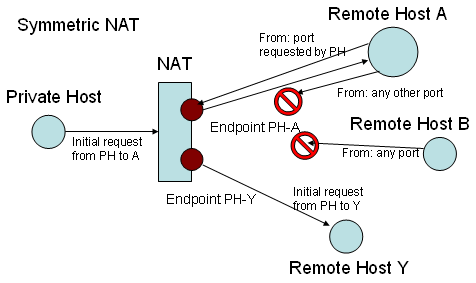

According to their behavior, NATs can be classified into four types:

- Full Cone

- Restricted Cone

- Port Restricted Cone

- Symmetric

Router configuration

todo

Port forwarding

Ein probates Mittel für NAT-Traversal ist die manuelle Konfiguration des NAT-Routers. Dabei wird der NAT-Router so konfiguriert, dass er bestimmte Datenpakete an einen bestimmtem lokalen Rechner weiterleitet. Die Weiterleitung bestimmt der NAT-Router in der Regel auf Grund des Zielportes im Datenpaket. Der NAT-Router benötigt somit für das Port-Forwarding eine Portnummer (bzw. einen Portbereich) und die IP-Adresse des lokalen Rechners. Über diese feste Weiterleitung anhand der Portnummer ist der lokale Rechner außerhalb des Netzwerkes über diesen festgelegten Port (bzw. Portbereich) erreichbar (NAT-Traversal).

Der grosse Vorteil vom Port-Forwarding ist, dass es für viele Anwendungsfälle die einzig wirklich funktionierende NAT-Traversal-Technik darstellt. Demgegenüber stehen jedoch einige Nachteile:

- Andere lokale Rechner können durch die feste Zuordnung von einer Portnummer zu einen bestimmten Rechner, diesen Port nicht nutzen

- viele Anwendungen wählen den Port dynamisch, so dass dieser vorher schwer bestimmbar ist oder wählen einen Port aus einem grossen Port-Bereich

- Port-Forwarding setzt einen Zugang zum Router und technisches Verständnis voraus

UPnP

Eine andere Möglichkeit, ausgehend vom Port-Forwarding, ist den Vorgang der Routerkonfiguration zu automatisieren. Der Gedanke hierbei ist, dass Anwendungen auf den lokalen Rechnern den NAT-Router nach ihren Bedürfnissen steuern können. Die Bedürfnisse hierbei sind vor allem das Port-Forwarding und die Kenntnis darüber welche öffentliche IP-Adresse der NAT-Router besitzt. Es wird bei dieser Technik davon ausgegangen, dass sich im lokalen Netzwerk, indem sich die loklalen Rechner und der NAT-Router befinden, niemand mit böswilliger Absicht aufhält und der Zugang zum lokalen Netzwerk entsprechend gesichert ist. Durch diese Technik werden einige Nachteile des manuellen Port-Forwarding behoben. Realisiert werden kann diese NAT-Traversal-Technik durch "Universal Plug and Play" (UPnP). UPnP wurde 1999 durch das UPnP-Forum spezifiziert und wird von diesem ständig weiterentwickelt. UPnP wurde nicht für NAT-Traversal entwickelt, sondern für eine herstellerunabhängige Steuerung von elektronischen Geräten über ein IP-Netzwerk und kann somit für NAT-Traversal benutzt werden. UPnP wurde so entworfen, dass es bereits vorhandene Netzwerkprotokolle und Datenformate, wie HTTP, SSDP, XML, usw. benutzt. Voraussetzung für die Implementierung von UPnP auf einem Gerät ist, dass auf diesem ein Betriebssystem und eine Netzwerkschnittstelle vorhanden ist. Viele im Handel erhältliche NAT-Router unterstützen bereits UPnP, sodass NAT-Traversal mittels UPnP bereits in Anwendung ist. Der allgemeine Ablauf für eine Kommunikation zwischen einem UPnP-Gerät (z.B. NAT-Router) und einem UPnP-Kontrollpunkt (z.B. lokaler Rechner) sieht im Groben folgendermaßen aus:

- Das UPnP-Gerät macht sich und seine Dienste im lokalen Netzwerk über Multicast bekannt. Der UPnP-Kontrollpunkt erhält über diese Multicast-Nachrichten (Simple Service Discovery Protocol) Information darüber, um was für ein Gerät es sich handelt (z.B. Internet Gateway Device, Printer Device, HVAC (heating, ventilation, air conditioning) usw.) und unter welcher Adresse er detaillierte Informationen über das Gerät erhalten kann.

- Der UPnP-Kontrollpunkt kann sich über diese Adresse die detaillierte Geräte- und Dienstbeschreibung (XML) vom Gerät holen.

- Anhand dieser Informationen wird der Kontrollpunkt in die Lage versetzt, das Gerät zu steuern. Der Kontrollpunkt kann nun über spezielle Nachrichten (SOAP) Aktionen aufrufen (z.B. AddPortMapping).

Aufgrund der vom UPnP-Forum standardisierten Geräte kann diese Kommunikation mit einem UPnP-Gerät durch eine Client-Anwendung ausgeführt werden.

STUN

todo

TURN

todo

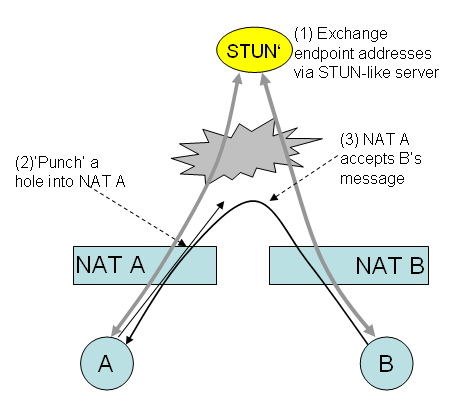

Hole punching

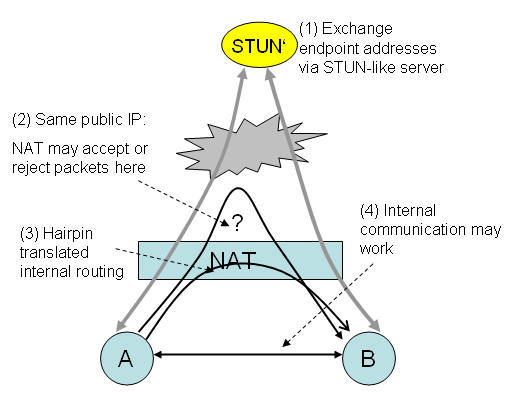

Conclusion: hole punching is not a cure-all for traversing NATs, but works fine for Cone-type NATs. Symmetric NATs cannot be traversed by using these simple methods.

Hairpin translation is a special case for hole punching and may allow direct communication for clients behind the same symmetric NAT. If all that does not work, the fallback strategy is to establish relayed connections using the TURN protocol.

NAT and Voice over IP

todo

Refereces

- Ford, Srisuresh, Kegel: Peer-to-Peer Communication Across Network Address Translators (link)

- Rosenberg, Huitema, Mahy: Traversal using relay NAT (TURN), Internet Draft (link)

- Rosenberg, Weinberger, Huitema, Mahy: STUN – simple traversal of user datagram protocol (UDP) through network address translators (NATs), March 2003, RFC3489 (link)

- Rosenberg: Interactive Connection Establishment (ICE), Internet Draft (link)

- Schulzrinne: diverse documents concerning NAT and SIP, e.g. NAT Types.pdf (NAT and SIP)

- STUN Client und Server (link)